Guide By – The Elder Abuse Attorney Los Angeles Residents Can Count On

This firm’s principal and founder, Dmitriy Cherepinskiy, is the elder abuse attorney Los Angeles senior citizens can rely on to fight for justice on their behalf. He is a zealous advocate on behalf of elderly and dependent adult victims of elder abuse and neglect. He is well known as a Los Angeles nursing home neglect lawyer, and he is respected by his peers, insurance companies, and clients. Dmitriy is a former defense attorney who represented nursing homes and assisted living facilities in Elder Abuse and Neglect cases.

This firm’s principal and founder, Dmitriy Cherepinskiy, is the elder abuse attorney Los Angeles senior citizens can rely on to fight for justice on their behalf. He is a zealous advocate on behalf of elderly and dependent adult victims of elder abuse and neglect. He is well known as a Los Angeles nursing home neglect lawyer, and he is respected by his peers, insurance companies, and clients. Dmitriy is a former defense attorney who represented nursing homes and assisted living facilities in Elder Abuse and Neglect cases.

As an experienced Los Angeles nursing home neglect lawyer, Mr. Cherepinskiy possesses a unique insight into the insurance defense industry and the inner workings of elder care institutions. He also has extensive litigation, courtroom, and trial expertise. All these factors make Dmitriy and his firm a formidable force in the fight for the rights, health and safety of elderly and dependent adult residents and patients of residential care and skilled nursing facilities throughout California. Cherepinskiy Law Firm utilizes cutting-edge technology and innovative legal strategies to handle every case from the initial investigation through the trial.

Statistics Regarding Elderly Population and Elder Abuse

Statistical analysis and research show the following data:

- Currently, “Baby Boomers” represent the fastest-growing elderly population in America, and this effect is expected to last for several decades.

- Elderly individuals who are 85 years old and older constitute the fastest-growing segment of population in the U.S. It is estimated that, between 2010 and 2050, the number of elderly people aged 85 years and older will more than triple.

- In 2010, the U.S. Census demonstrated that the number of individuals aged 65 and older was 40.30 million. This number, which represented approximately 13 percent of the population, was the largest number ever recorded in the history of conducting census analysis in the United States.

- It is expected that, by 2050, one fifth (20%) of the population of the United States will consist of individuals aged 65 years and older.

- Analysts estimate that, each year, 10% of America’s elderly suffer some form of neglect or abuse.

California’s Nursing Homes and Assisted Living Facilities Provide Care to Thousands of Seniors

At some point, many elderly people reach a stage in their life when they cannot care for themselves anymore. Well over a million of American seniors reside in nursing homes and assisted living facilities.

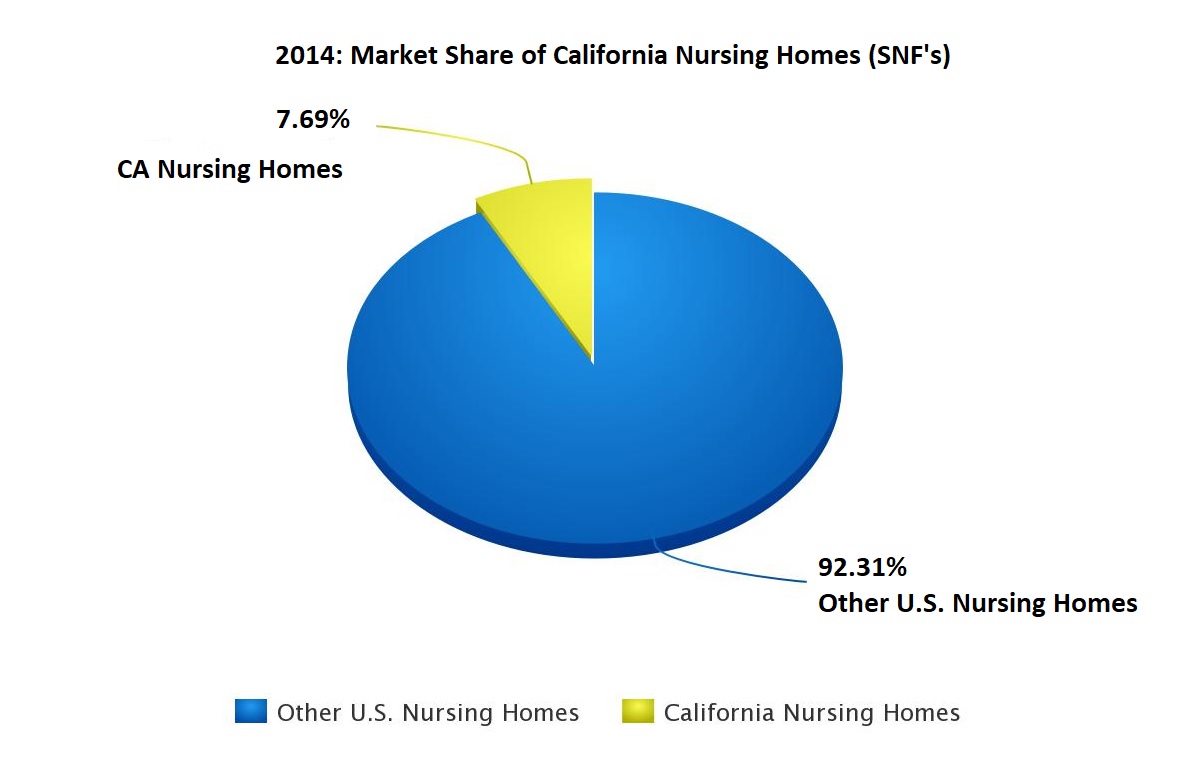

According to the statistical data from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Service (CMS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), California Association of Health Facilities (CAHF), and California Assisted Living Association (CALA), in 2014:

- There were over 15,600 nursing homes in the United States. California had more than 1,200 such facilities, which represented almost 8% of the total number – higher than any other State in the U.S. California skilled nursing facilities, licensed by the Department of Public Health, provide care and treatment to over 350,000 patients on an annual basis.

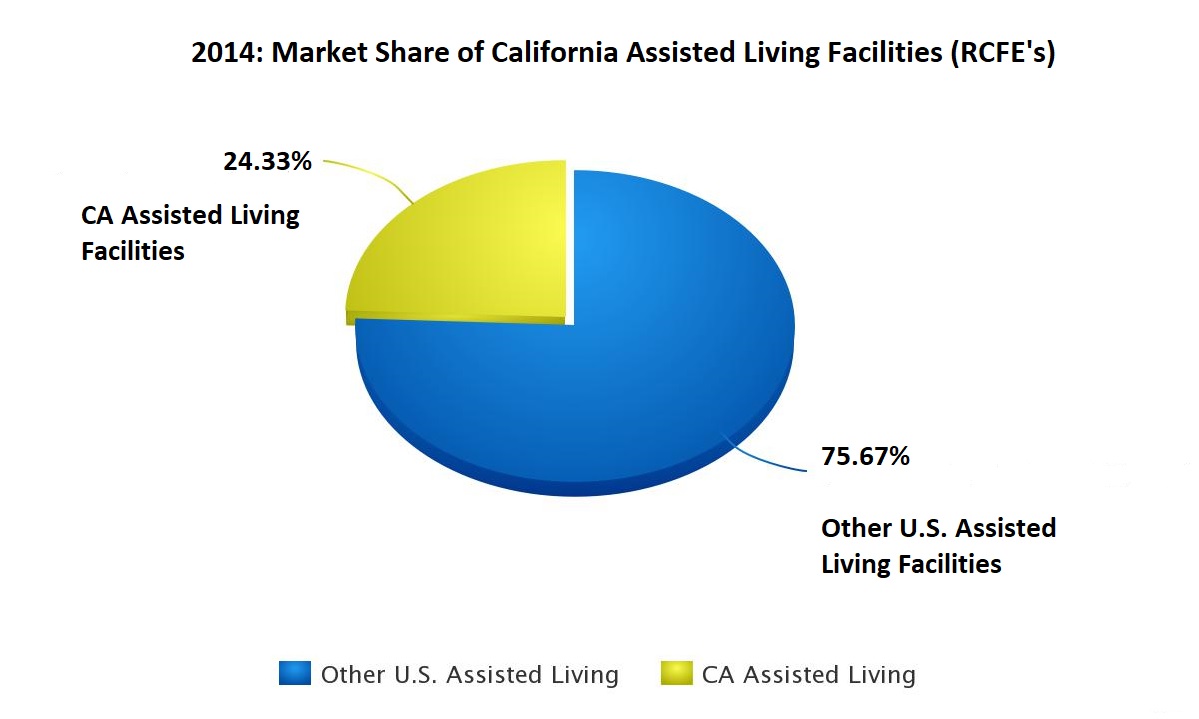

- There were more than 30,000 assisted living facilities in the U.S., of which over 7,300 (close to 25%) were located in the Golden State. Every year, California residential care facilities for the elderly, licensed by the Department of Social Services, serve as a home for more than 170,000 residents.

Clearly, owners and operators of California nursing homes and assisted living facilities have a significant share of the national senior care market. Nursing homes and assisted living facilities constitute a multi-billion-dollar industry, and it is expected to grow even further. According to the 2003 Report to Congress by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, by 2050, the total number of long-term care service recipients (such as nursing home patients and assisted living residents, as well as home care patients) is likely to reach 27 million individuals – i.e. virtually double compared to the 15 million people who used these services at the turn of the 21st century. This projection is based on the fact that older people now comprise the largest segment of the population in the United States, and the number of senior citizens who need care keeps growing fast.

California Elder Abuse and Neglect Law

The elderly are also the most helpless and vulnerable people in our society. Fortunately, California law is on the side of elders. Cherepinskiy Law Firm, as a Los Angeles elderly abuse lawyer, has the knowledge, skills, and resources to make sure the offenders who violate the law are brought to justice.

The elderly are also the most helpless and vulnerable people in our society. Fortunately, California law is on the side of elders. Cherepinskiy Law Firm, as a Los Angeles elderly abuse lawyer, has the knowledge, skills, and resources to make sure the offenders who violate the law are brought to justice.

In 1982, the California Legislature enacted the Elder Abuse and Dependent Adult Civil Protection Act (“EADACPA” and the “Elder Abuse Act” interchangeably). California Welfare & Institutions Code § 15600, et seq. At that time, the scope of the Elder Abuse Act covered investigations and reporting of elder abuse, as well as issues related to elder abuse as a criminal offense. The Legislature recognized that dependent adults and elders could become victims of neglect, abuse, or abandonment and that the state of California had a duty to protect these vulnerable individuals.

In 1991, the California Legislature expanded the scope of the Elder Abuse Act and added provisions, which encouraged victims of elder and dependent adult abuse and neglect and their successors in interest to pursue claims in civil courts. As discussed below, as long as a higher burden of proof is satisfied, the revised law allows recovery of pre-death pain and suffering and certain “enhanced” remedies such as attorney’s fees and punitive damages.

Currently, pursuant to the EADACPA, abuse of an elder or a dependent adult includes:

- Neglect,

- Physical Abuse,

- Isolation,

- Abandonment,

- Abduction,

- Financial Abuse,

- Circumstances were a care custodian deprives an elderly or dependent adult of services or goods, which are needed to avoid mental suffering or physical harm, and

- “other treatment with resulting physical harm or pain or mental suffering.”

California Welfare & Institutions Code § 15610.07. An “elder” is any individual who is 65 years old or older. A “dependent adult” is any person, ages 18 to 64, who:

(1) has limitations, which are mental or physical in nature, and which restrict this person’s ability to protect his or her rights or perform normal activities; or

(2) is admitted as an inpatient to a 24-hour health facility.

California Welfare & Institutions Code §§ 15610.27 and 15610.23.

Within the meaning of the EADACPA (the Elder Abuse Act), the specific types of the most common wrongdoing are defined as follows:

- “Physical abuse” includes, but is not limited to, assault, battery, and the use of a “physical [restraint] or chemical restraint … [f]or any purpose not authorized by the physician and surgeon.” California Welfare & Institutions Code § 15610.63.

- “Neglect”, in turn, refers to the “negligent failure” by any person who has custody or care of a dependent adult or an elderly person to exercise the level of care that would be exercised by a reasonable person in a similar position. California Welfare & Institutions Code § 15610.57(a). Neglect includes such misconduct as the failures to “assist in personal hygiene, or in the provision of food, clothing, or shelter”, “prevent malnutrition or dehydration,” and otherwise protect from “health and safety hazards.” California Welfare & Institutions Code § 15610.57(b).

- “Abandonment” occurs when a care custodian forsakes or deserts a person, when a reasonable individual would have continued to provide custody and care under the same circumstances. California Welfare & Institutions Code § 15610.05.

- “Financial abuse” takes place when an entity or an individual does any of the following to a dependent adult or an elderly person (1) with an intent to defraud or for a wrongful use, or both, or (2) with the use of undue influence:

-

- Obtains, appropriates, takes, retains, or secretes personal or real property; or

- Provides assistance in appropriating, taking, retaining, or secreting personal or real property.

California Welfare & Institutions Code § 15610.30.

Both nursing homes and assisted living facilities must comply with the provisions of the Elder Abuse Act. In addition, both types of institutions are regulated by, and have to follow, TITLE 22 of the California Code of Regulations (CCR). Patients of skilled nursing facilities are protected by the Patients’ Bill of Rights, which is spelled out in Section 72527 of Title 22 of the CCR and includes the following patient rights:

- to be free from mental and physical abuse;

- to be treated with consideration, respect and full recognition of dignity and individuality; and

- to be free from psychotherapeutic drugs and physical restraints used for the purpose of patient discipline or staff convenience and to be free from psychotherapeutic drugs used as a chemical restraint.

Pursuant to California Health and Safety Code § 1430(b), violations of the Patients’ Bill of Rights subjects nursing homes to monetary penalties, costs, and attorney’s fees. Once you consult with a Los Angeles elder neglect attorney, all applicable laws and regulations will be analyzed in terms of their application to the specific case at hand.

In addition, pursuant to California Evidence Code § 669, a person’s violation of a statute or a regulation will result in a presumption that the person failed to exercise “due care”. This presumption is commonly referred to as “negligence per se.” In order to qualify as “neglect” pursuant to the Elder Abuse Act, the conduct in question must rise above mere negligence. Nevertheless, as discussed above, “neglect” means the “negligent failure” by a care custodian to exercise the degree of care that would be exercised by a reasonable person in a similar position. California Welfare & Institutions Code § 15610.57(a). Therefore, it can be argued that violations of certain statutes and regulations warrant a presumption of “neglect” pursuant to Evidence Code § 669. In the context of elder abuse and neglect, these regulations and statutes include, but are not limited to, the following:

- Title 22 of California Code of Regulations, § 87100 et seq. [residential care facilities for the elderly];

- Title 22 of California Code of Regulations, § 72301, et seq. [skilled nursing facilities];

- California Penal Code § 368 and other criminal statutes;

- California Health & Safety Code § 1599.65 [admission contracts for long term care facilities];

- California Health & Safety Code § 1417, et seq. [also known as “the Long-Term Care, Health, Safety, and Security Act of 1973”];

- 42 U.S.C. § 1395i-3 [Federal statute setting forth requirements pertaining to quality of care in nursing homes];

- 42 CFR § 483.1, et seq. [the Code of Federal Regulations applicable to skilled nursing facilities receiving payments from Medicare] and specific examples subject to the Federal regulations:

-

- 42 CFR § 483.25(d) [accidents and hazards];

- 42 CFR § 483.25(n) [bed rails];

- 42 CFR § 483.25(g) [malnutrition and dehydration];

- 42 CFR § 483.25(b)(1) [pressure ulcers];

- 42 CFR § 483.20 [resident assessments and care planning];

- 42 CFR § 483.70 [administration and medical record maintenance]; and

- 42 CFR § 483.35 [nursing services and staffing requirements].

Is Elder Neglect the Same as Negligence? Ask Los Angeles Nursing Home Neglect Lawyer

Elder Neglect is significantly different from Medical Malpractice / Negligence. When proving elder neglect, the level of culpability that must be established is higher than ordinary negligence.

Under California law:

- “There can be no claim for abuse of a dependent adult unless a plaintiff can demonstrate by clear and convincing evidence that the defendant is guilty of something more than negligence.”

- The acts prescribed by the Elder Abuse Act do not involve “acts of simple professional negligence”. Instead, the subject misconduct refers to neglect or abuse, which is committed with a level of culpability that is “greater than mere negligence.”

Delaney v. Baker, 20 Cal. 4th 23, 31-32 (1999) (emphasis added).

Only a highly experienced Los Angeles nursing home abuse lawyer, such as Dmitriy Cherepinskiy and his firm, can engage in the battle with nursing homes, assisted living facilities, as well as the insurance companies and lawyers defending them.

Notable Elder Abuse Case Law: As Explained by – Los Angeles Elder Abuse Attorney

Ever since 1991, when the Elder Abuse Act was revised to allow for the recovery of “heightened” remedies such as pre-death pain and suffering, attorney’s fees, and punitive damages, this area of the law became a hot battleground for disputes involving the difference between mere professional negligence and elder and dependent adult abuse and neglect. For the defense, the main goal has been to argue that the alleged acts or omissions amount to nothing more than simple professional negligence. The favorite argument made by defense lawyers is as follows: “Just because the plaintiff happens to be older than 65 years of age or is a dependent adult – it does not mean that every alleged negligent wrongdoing automatically becomes abuse or neglect within the meaning of the Elder Abuse Act”.

In the 1990’s, it was also common for health care providers to argue that the Elder Abuse Act was not applicable to them no matter how egregious their actions were. Throughout the state, in the absence of California case law interpreting the elder abuse statute, trial courts reached different and inconsistent results. Courts and litigants desperately needed guidance. Starting with the Delaney v. Baker case in 1999, California Supreme Court and the Court of Appeals have been interpreting the Elder Abuse Act. As the Los Angeles elder abuse attorney, Cherepinskiy Law Firm provides the following discussion of the notable California elder abuse cases and published opinions. The cases are discussed in chronological order.

Delaney v. Baker

In 1999, the California Supreme Court issued its decision in Delaney v. Baker, 20 Cal. 4th 23 (1999). The Court provided the much-needed guidance in terms of: 1) the distinction between “elder abuse and neglect” and “professional negligence” and 2) the issue of whether or not providers of health care services were exempt from the heightened remedies of the Elder Abuse Act. The Delaney opinion became the seminal case in the elder abuse arena, and it served as a significant triumph for victims of elder and dependent adult abuse and neglect.

In Delaney, the plaintiff filed an action against a defendant skilled nursing facility alleging, among other things, wrongful death and elder neglect pursuant to the Elder Abuse Act. The plaintiff alleged that her mother, an 88-year-old woman, had a broken ankle and was regularly left lying in her feces and urine for extended periods of time. All complaints to the administration were ignored. At the time of her death, the plaintiff’s mother had pressure ulcers (bedsores) on her buttocks, feet, and ankles. Some of the bedsores were so deep that the bone was exposed. The jury returned a verdict in plaintiff’s favor and found that the defendant nursing home committed “reckless neglect”. The plaintiff was awarded heightened remedies in the form of damages for the decedent’s pre-death pain and suffering as well as attorney’s fees and costs pursuant to California Welfare and Institutions Code § 15657. The defendant skilled nursing facility appealed, and the Court of Appeals affirmed the decision at the trial court level. So, the defendant took the case up to the California Supreme Court.

On appeal, the defendant nursing home contended that the enhanced remedies of section 15657 did not and could not apply to cases against health care providers, no matter how reckless their misconduct was. Specifically, the defendant argued that, pursuant to California Welfare and Institutions Code § 15657.2, all cases directly related to the provision of professional services by health care providers were subject to other statutes that limited recovery, such as MICRA [Medical Injury Compensation Reform Act].

The defendant relied heavily on the California Supreme Court’s decision in Central Pathology Serv. Med. Clinic, Inc. v. Superior Court, 3 Cal. 4th 181 (1992). In Central Pathology, the Court commented that, in the context of legal actions against health care providers, certain MICRA provisions could apply to intentional torts and its application was not limited to cases involving solely professional negligence. Central Pathology, 3 Cal. 4th at 192. Based on Central Pathology, the “default” defense argument at that time was as follows: if a case arises out of the provision of services by a health care provider, then all recoverable damages are automatically subject to MICRA and no other damages can be awarded.

In Delaney, the California Supreme Court unequivocally noted that its decision in Central Pathology did not “universally define” the concept of professional negligence or what it means when a case is “based on professional negligence” [as that phrase is used in Welfare and Institutions Code § 15657.2]. The Delaney court rejected the argument that the enhanced remedies of the Elder Abuse Act did not apply in cases against health care providers. Specifically, the California Supreme Court disagreed with the defendant’s argument that section 15657.2 applied to all cases directly related to the provision of professional services by health care providers. The Court stressed that it would be an “anomaly” to subject a “recklessly neglectful” custodian of an elderly individual or dependent adult to the enhanced remedies of section 15657 “only if” that custodian was “not a licensed health care professional”. The California Legislature did not intend such an anomaly. Delaney, 20 Cal. 4th at 35.

The Court held that, regardless of a defendant’s status as a health care provider, if the defendant’s neglect is reckless or committed with malice, oppression, or fraud, then: (1) the level of the defendant’s culpability rises above mere “professional negligence” and (2) the misconduct is subject to the heightened remedies of California Welfare and Institutions Code § 15657. Id.

White v. Ultramar

In order to recover enhanced remedies (e.g. attorney’s fees and punitive damages) against a defendant assisted living facility or skilled nursing facility, or its parent corporation, the plaintiff must meet the requirements of California Civil Code § 3294(b). The “managing agents” of long-term care facilities are administrators, directors of nursing services, and other individuals who make care-related decisions and are involved in the creation or changing of the facility’s policies and procedures. The California Supreme Court opinion in White v. Ultramar, 21 Cal. 4th 563 (1999) contains a detailed analysis of the “managing agent” doctrine.

Mack v. Soung

In Mack v. Soung, 80 Cal. App. 4th 966, 974 (2000), plaintiff asserted an elder abuse cause of action against a defendant physician. Plaintiff alleged that the defendant doctor concealed the fact that his patient had a pressure ulcer (bedsore), objected to the patient’s hospitalization, and abandoned the elderly patient “in her dying hour of need”. The defendant physician made an argument that, just because he was a physician – i.e. a health care provider – a cause of action for elder abuse could not be asserted against him. The trial court sustained the defendant’s demurrer as to the elder abuse claim.

The California Court of Appeals reversed the trial court’s ruling and held that the trial court abused its discretion. The Mack court concluded that health care providers, including physicians, could face liability pursuant to the Elder Abuse Act for their neglect in the provision of medical services. Specifically, the court held that both types of professionals – care custodians and health care providers – have the responsibility for the safety, health and welfare of dependent adults of elders. Mack v. Soung, 80 Cal. App. 4th at 974.

The above holding in the Mack v. Soung case, however, is not citable anymore. Of course, it is still well-settled that health care providers can be liable for elder abuse. However, in order to be subject to the Elder Abuse Act, a healthcare provider must also be a plaintiff’s care custodian. Sixteen years after the Mack v. Soung opinion was issued, in Winn v. Pioneer Med. Grp., Inc., 63 Cal. 4th 148, 164 (2016), the California Supreme Court stated that it disapproved Mack v. Soung. The Court’s disapproval was limited to the Mack v. Soung court’s holding that claims of neglect pursuant to the Elder Abuse Act could be asserted against a doctor irrespective of his or her relationship with an elderly patient (i.e. regardless of whether or not the doctor was in a custodial or caretaking with the patient).

Benun v. Superior Court

In Benun v. Superior Court, 123 Cal. App. 4th 113 (2004), the main issue presented to the California Court of Appeals was as follows: Is the one-year statute of limitations pursuant to California Code of Civil Procedure § 340.5 [which applies to professional negligence actions against health care providers] applicable to cases involving elder abuse and neglect? The court stressed that the laws applicable to professional negligence cases did not govern acts of custodial elder abuse. Citing the legislative history of the Elder Abuse Act, the Benun court held that section 340.5 was not applicable to elder abuse cases.

The Court of Appeals decided that California Code of Civil Procedure § 335.1 “facially” applied to elder abuse cases and provided a two-year statute of limitations. In general, section 335.1 covers cases alleging:

- Assault,

- Battery, or

- Death or Injury of a person, which is caused by another person’s “wrongful act or neglect”.

The court also commented that the statute of limitations period in elder abuse actions was subject to being tolled due to “insanity” pursuant to California Code of Civil Procedure § 352 [which covers situations where the plaintiff lacks the legal capacity to engage in a decision-making process]. Theoretically, an argument can be made that section 352 tolls the statute of limitations in those elder abuse and neglect cases where the plaintiff had a condition affecting his or her mental capacity (e.g. Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, intellectual disability, and other conditions). Benun v. Superior Court, 123 Cal. App. 4th 113, 125-127 (2004).

Please note: This discussion of the Benun case is simply a case discussion, and it should not be interpreted as legal advice or a representation that it is 100% certain the statute of limitations for elder abuse cases against healthcare providers is two (2) years. This area of the law is still evolving. Some plaintiffs have made creative arguments that California Code of Civil Procedure § 338 [which provides for a three-year statute of limitations in statutory causes of action] applies to elder abuse cases. It is extremely risky to take such a position. In fact, some defendants may still argue that the Benun decision was mere “dicta” and that the one-year statute of limitations per section 340.5 does apply to elder abuse cases. Plaintiffs and their attorneys should make their own assessments of facts applicable to their specific cases and make appropriate decisions regarding the applicable statute of limitations.

Covenant Care v. Superior Court

In Covenant Care, Inc. v. Superior Court, 32 Cal. 4th 771 (2004), the California Supreme Court took another opportunity (the first one was in in the Delaney case) to further define elder abuse. The main issue presented to the Court was whether or not California Code of Civil Procedure § 425.13(a) was applicable to elder abuse actions. Section 425.13 states that, in any professional negligence claim against a health care provider, no claim for punitive damages can be alleged unless the court allows it based on the plaintiff’s demonstration of a “substantial probability” of prevailing on the punitive damages claim pursuant to California Civil Code § 3294.

In its detailed opinion, the California Supreme Court held that section 425.13(a) does not apply to claims for punitive damages in actions brought pursuant to the Elder Abuse Act. Following its analysis in the Delaney case, the Court discussed the difference between mere professional negligence (which does not provide for any enhanced remedies) and elder and dependent adult abuse and neglect (which involves the level of culpability greater than negligence and does allow recovery of enhanced remedies). Covenant Care, 32 Cal. 4th at 784, 790.

The Covenant Care Court noted once again that some health care facilities, such as nursing homes, happen to provide both professional medical care and custodial services (the Court made the same comment in Delaney, 20 Cal. 4th at 34). Nevertheless, the functions of (1) a provider of custodial care and (2) a health care provider – are distinctly different and should not be confused. The Court stressed that elder abuse claims are not asserted against health care providers in that capacity. Instead, elder abuse claims apply to providers of custodial care who engage in elder abuse, even if they, incidentally, also happen to be health care providers. Covenant Care, 32 Cal. 4th at 786.

Finally, citing Delaney, the Court noted that the definition of “neglect” refers to the failure to provide medical care for mental and physical health needs, as opposed to the affirmative undertaking of medical services. Covenant Care, 32 Cal. 4th at 783 (citing Delaney, 20 Cal. 4th at 34). Seven years later, in 2011, in Carter v. Prime Healthcare, the California Court of Appeals heavily focused on this distinction.

Sababin v. Superior Court

In Sababin v. Superior Court, 144 Cal. App. 4th 81 (2006), the unfortunate 38-year-old patient was suffering from Huntington’s Chorea, a condition that placed the patient at a higher the risk of skin deterioration. The patient died as a result of infected to a sacral pressure ulcer. The plaintiffs asserted a dependent adult abuse cause of action. The plaintiffs alleged that the defendant nursing home did not satisfy its obligation to meet the patient’s basic needs by failing comply with the care plan, which required daily checks of the patient’s skin. The trial court found that there was no evidence that the defendant’s misconduct rose above mere professional negligence and granted the motion for summary adjudication as to the dependent adult abuse cause of action. Sababin v. Superior Court, 144 Cal. App. 4th 81, 83-85 (2006). The plaintiffs appealed.

On appeal, the defendant nursing home argued that, unless there is a “total absence of care”, a facility cannot face any liability for dependent adult abuse. The Court of Appeals disagreed. The Sababin court held that, “if some care is provided”, it will not necessarily mean that a care facility will avoid liability for dependent adult abuse. The court provided several examples:

- If a care facility is aware that it has an obligation to provide certain care on a “daily basis” but, instead, choses to provide the required care “sporadically”; or

- If a care facility has an obligation to provide “multiple types” of specific care but, instead, provides only “some types” of that required care. In this case, it will be considered that the facility withdrew care.

The Sababin court also stressed that if a care facility engages in a “repeated withholding of care”, it would constitute a “significant pattern” and would indicate that the pattern was due to either deliberate indifference or choice. Sababin, 144 Cal. App. 4th at 90.

Finally, with respect to the facts of the Sababin case, the Court of Appeals indicated the following: the jury could find that, if a facility ignores a care plan and does not inspect the skin condition of a resident with Huntington’s Chorea, it demonstrates a deliberate disregard of a high probability that the resident would be injured [i.e. reckless neglect]. Id. Of course, not every nursing home resident suffers from Huntington’s Chorea. However, elderly and dependent adult residents of long-term care facilities frequently suffer from various conditions that, in the absence of proper or consistent care, predispose them to injuries. Therefore, the above holding in Sababin can be applied to cases involving other factual scenarios.

C.R. v. Tenet Healthcare

As an alternative theory to vicarious liability (also referred to as “respondeat superior”), a long-term care facility may face liability for elder abuse based on the doctrine of “ratification”. This theory of liability applies to nursing homes, assisted living facilities, as well as their parent corporations. The California Court of Appeals opinion in C.R. v. Tenet Healthcare Corp., 169 Cal. App. 4th 1094 (2009) providers a very useful discussion of this concept.

Specifically, the C.R. v. Tenet court held that an employer can be held liable for the acts of its employees if the employer either (1) authorized the wrongful act before it occurred or (2) subsequently ratified the inappropriate conduct after its occurrence. Ratification may be evidenced by the failure to discharge an employee who is unqualified or who has committed an act of misconduct. In addition, the doctrine of ratification applies in cases where an employer fails to perform an investigation or respond to the complaint of an employee’s wrongdoing. C.R. v. Tenet, 169 Cal. App. 4th at 1110.

Carter v. Prime Healthcare

In the case of Carter v. Prime Healthcare Paradise Valley, LLC, 198 Cal. App. 4th 396 (2011), the Court set forth the factors required to constitute neglect within the meaning of the Elder Abuse Act.

In Carter, the plaintiffs alleged that their father, Roosevelt Grant (“Mr. Grant”) died because the hospital failed to administer antibiotics necessary to treat Mr. Grant’s pneumonia and the hospital’s crash cart did not contain the appropriate size endo-tracheal tube. The plaintiffs also contended that bags with fluids were being injected into Mr. Grant, and the hospital staff searched for a properly-sized endo-tracheal tube. The Carter court noted that the hospital’s actions might amount to professional negligence, but the hospital’s conduct did not constitute neglect within the meaning of the Elder Abuse Act. The court noted that the hospital did not withhold or deny any treatment or services to Mr. Grant. Although the hospital’s efforts were not successful, the hospital did actively undertake to provide care and treatment aimed to save Mr. Grant’s life. Id. at 408.

The Carter Court stressed that, in cases involving medical care provided to an elderly or dependent adult, the concept of “neglect” means “the failure to provide medical care”, as opposed to the undertaking of medical services. In other words, an egregious withholding of medical care that is necessary for mental and physical health needs may constitute neglect. Id. at 404-405.

The Carter case sets forth the specific factors required to plead and establish a claim for “neglect” under the Elder Abuse Act. Specifically, the Carter court held that the plaintiff has to allege (and ultimately prove by clear and convincing evidence) specific facts showing that the defendant:

1) was responsible for meeting elder or dependent adult’s basic needs [e.g. hygiene, hydration, nutrition, or specific medical care];

2) had knowledge of those conditions, which made the dependent adult or elderly person unable to provide for her or his basic needs; and

3) withheld or denied those services or goods, which were necessary to meet the dependent adult or elderly individual’s basic needs [where the wrongdoing was committed either with knowledge that it was substantially certain the dependent adult or elder would get injured or with conscious disregard of the injury].

Carter, 198 Cal. App. 4th at 406-407.

The Carter court provided the following examples of other cases where the misconduct was sufficient to constitute “neglect” under the Elder Abuse Act (Id. at 405-406.):

- An elderly gentleman with Parkinson’s disease was a resident at a nursing home (skilled nursing facility). The facility: failed to provide this elderly man with the necessary medications; failed to provide him with sufficient water and food; left him completely unattended and without any assistance; left the man lying in his own excrement resulting in his pressure ulcers becoming infected; and failed to inform the elderly man’s children of his real condition [Covenant Care v. Superior Court above];

- An elderly (78-year-old) man became a resident at a nursing home where he was denied medical treatment and was restrained, beaten, and abused. [Smith v. Ben Bennett, Inc., 133 Cal. App. 4th 1507, 1512 (2005).]

- A skilled nursing facility was supposed to care for an elderly 90-year-old lady who was blind and had dementia. The facility restrained her using chemical and physical restraints, withheld food and water, failed to provide assistance with eating, bruised her, as well as threatened and screamed at the poor woman. [Benun v. Superior Court above]

- An 88-year-old elderly lady who had a fractured ankle was routinely left lying in her feces and urine for long periods of time, despite her complaints to the facility’s administration and staff and even to the long-term care ombudsman. As a result of this misconduct, the plaintiff developed bedsores (pressure ulcers) on her buttocks, ankles and feet that were so deep that her bone became exposed. [Delaney v. Baker above]

Fenimore v. UC Regents

In Fenimore v. Regents of Univ. of Cal., 245 Cal. App. 4th 1339, 1349 (2016), the California Court of Appeals held that a violation of staffing regulations can constitute “neglect” within the meaning of the Elder Abuse Act. Specifically, the Fenimore court stressed that the violation of staffing regulations [i.e. understaffing] can be sufficient to demonstrate neglect within the following definitions set forth in California Welfare & Institutions Code § 15610.57(b):

- a negligent failure to exercise the care, which would have been exercised by a reasonable person in a similar situation; and

- a failure to protect the elder or dependent adult from “health and safety hazards”.

Winn v. Pioneer Medical Group

In 2016, seventeen years after the Delaney case and twelve years after the Covenant Care case, the California Supreme Court re-visited the “elder abuse” area again. In Winn v. Pioneer Med. Grp., Inc., 63 Cal. 4th 148 (2016), the Court clearly and unequivocally stressed that it is the defendant’s relationship with a dependent adult or an elderly person that determines whether the defendant can be subject to a potential liability for elder neglect. The defendant’s expertise and professional standing are irrelevant in this context. Winn, 63 Cal. 4th at 158, 202.

Specifically, the Winn court concluded that a cause of action for neglect pursuant to the Elder Abuse Act requires a relationship of custodial or caretaking nature. A custodial or caretaking relationship is created when a defendant has a “significant responsibility” for attending to those basic needs of a dependent adult or elderly person that a completely competent and able-bodied adult would “ordinarily” be able to manage without any assistance. Winn, 63 Cal. 4th at 155. In other words, it does not matter whether a specific defendant is a health care provider or not. Unless the defendant had care or custody over the dependent adult or elder, this defendant cannot be subject to a claim of neglect pursuant to the Elder Abuse Act.

In Winn, the plaintiffs contended that defendants provided substandard medical treatment to an elder individual. The treatment was provided on an outpatient basis. The Court concluded that, without facts showing that the defendants had custodial or caretaking relationship with the elder, the allegations were not sufficient to allege neglect pursuant to the Elder Abuse Act. Winn, 63 Cal. 4th at 165.

This unequivocal opinion by the California Supreme Court “settles” the years-long dispute between the plaintiffs’ and defense lawyers regarding whether or not it is necessary to provide “custodial care” to be subject to the Elder Abuse Act. Unfortunately for plaintiffs, the Winn case makes it virtually impossible to assert an elder neglect cause of action against a physician, especially if the physician provided care and treatment in an outpatient setting. As discussed above, in Winn, the California Supreme Court explicitly disapproved Mack v. Soung to the extent it held that neglect could be alleged against a physician regardless of the physician’s custodial or caretaking relationship with an elderly patient. Winn, 63 Cal. 4th at 164.

Cherepinskiy Law Firm, as the Los Angeles elder abuse lawyer, firmly believes that familiarity with all developments in this field is key to obtaining successful outcomes for clients.

Nursing Homes and Assisted Living Facilities Provide Different Levels of Care

Despite their equal obligations to follow the law, the kind of care nursing homes and assisted living facilities are licensed to provide is quite different. Their formal names, as used by the California licensing and regulatory organizations, are as follows:

Nursing Homes

- Commonly used name – “Nursing Home”

- Formal name – “Skilled Nursing Facility (SNF)”

Assisted Living Institutions

- Commonly used name – “Assisted Living Facility”

- Formal name – “Residential Care Facility for the Elderly (RCFE)”

As their formal and informal names suggest, nursing homes and assisted living institutions provide two distinct levels of care. Residential Care facilities are designed to deliver constant supervision and care in a residential (home) environment for elderly people who need help with activities of daily living (ADLs), those with dementia, or receive hospice services. The main feature of RCFEs is that they do not provide 24-hour nursing care. Skilled Nursing facilities, on the other hand, must supply sufficient “skilled” staff to deliver 24/7 nursing care and medical treatment. The following are the key distinctions between these elder care facilities:

Differences Between Nursing Homes and Assisted Living Facilities

Setting:

- A nursing home is a medical facility.

- An assisted living facility is not licensed to provide medical care. It is a non-medical, residential care institution.

Licensing Status:

- A nursing home is licensed as a healthcare provider.

- An assisted living facility is not a healthcare provider.

Staff:

Nursing homes are stuffed with skilled and licensed nurses as follows:

- Registered nurses (RNs)

- Licensed vocational nurses (LVNs)

- Certified Nursing Assistants (CNAs)

Assisted living facilities, on the other hand, employ the following staff:

- Unlicensed low-skill caregivers

- Typically, there is only one in-house licensed nurse serving as a Clinical Care Director and /or Memory Care Director

Service Recipients are Considered:

- “Patients” – for nursing homes

- “Residents” – for assisted living facilities.

Typical Length of Stay:

- Nursing homes – unless a patient requires long term care, a typical length of stay is short term. Usually, there is a plan in place for a patient to return to home or assisted living after the rehabilitation.

- Assisted living – in general, this is a long-term arrangement. In most cases, the plan includes creation of a new “home” that provides assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs).

Services Provided:

Nursing homes provide the following medical services for acute and chronic care needs:

- Post-surgical rehabilitation

- Post-hospitalization rehabilitation

- Physical therapy

- Occupational therapy

- IV medications

- Respiratory assistance (e.g. ventilators)

Assisted living facilities, on the other hand, provide non-medical help with activities of daily living (ADLs):

- Social support

- Mobility / ambulation, transfers (bed, chair, wheelchair)

- Eating, dressing, bathing, toilet needs

- Mental health issues (dementia, depression)

- Management of Medications

- Management of Finances

Payment for Service:

For nursing homes, most short-term stays are covered by Medicare. In some cases, long-term care can be financed by:

- Long-term care insurance

- Medicaid

- Personal and Family resources

For assisted living facilities, the vast majority of residents are on a “Private Pay” basis – i.e. the services are paid for by the residents or their families. A limited number of residents receive financial assistance through the following public benefits:

- Long-term care insurance

- SSI (Supplemental Security Income)

- SSD (Social Security Disability)

- Assisted Living Waiver (provided by Medicare)

Both kinds of facilities aggressively market themselves using images of smiling elderly people with a caring hand of an attentive staff member on their shoulder. This advertising evokes trust on the part of senior citizens and their families. The sad reality, however, frequently differs from the colorful brochures and pamphlets printed by nursing homes and assisted living facilities. Unfortunately, the hunt for profits leads these institutions to cut corners. Nursing home abuse is rampant. The mission of Cherepinskiy Law Firm, as the Los Angeles elder abuse attorney, is to engage in the battle for the rights of the victims.

Typical Signs of Elder Abuse and Elder Neglect

Among skilled nursing facilities, the most prevalent cost-saving technique is understaffing. As a result, overworked, underpaid, and frustrated nurses either don’t have the incentive to or are simply physically unable to provide adequate medical care to elderly patients.

Among skilled nursing facilities, the most prevalent cost-saving technique is understaffing. As a result, overworked, underpaid, and frustrated nurses either don’t have the incentive to or are simply physically unable to provide adequate medical care to elderly patients.

Many RCFEs attempt to steer elderly people with acute care needs away from nursing homes, and market themselves as providing services that they are, in fact, not capable of providing. Residential care facilities are notorious for accepting / maintaining residents who need a higher level of care than an assisted living can provide.

For instance, an assisted living resident may have significant physical and/or mental limitations that require round-the-clock care (i.e. a bed-ridden resident who requires constant turning to prevent bed sores, or a person with dementia who needs regular monitoring and redirection). This resident must be transferred to a facility that is equipped to provide a higher level of care, such as a nursing home. However, the assisted living would keep the resident in order to continue billing for their services, especially if this is a “private pay” resident.

Hiring unqualified caregivers is another money-saving approach routinely utilized by residential care facilities. Frequently, inadequately trained caregivers are unable to recognize the signs and symptoms of a resident’s rapidly declining physical and mental functioning, and some are unable to provide the very basic ADL services.

Hiring unqualified caregivers is another money-saving approach routinely utilized by residential care facilities. Frequently, inadequately trained caregivers are unable to recognize the signs and symptoms of a resident’s rapidly declining physical and mental functioning, and some are unable to provide the very basic ADL services.

The financial shortcuts used by Assisted Living facilities and Nursing Homes often lead to serious, and in some tragic cases, fatal consequences. When elder abuse or neglect in the hands of a nursing home or an assisted living facility causes the death of a loved one, the surviving family (typically, spouses, children, or grandchildren) may pursue a Wrongful Death action.

For example, falls are some of the most common causes of death of assisted living residents and nursing home patients. When an elderly person is considered a “fall risk”, the facility must implement a care plan with appropriate fall precautions – i.e. low beds, floor mats, non-skid socks, and bed alarms. When, due to elder neglect and inappropriate cost-saving methods, proper safety precautions are not followed, tragic and fatal falls can occur. Bone density decreases with age, and order patients commonly develop osteoporosis – a condition, which makes bones fragile and more susceptible to fractures (bones breaking). Medical literature shows that women are especially predisposed to developing osteoporosis.

A hip fracture, for instance, is a very common result of a fall. It multiplies the risk of death and, depending on the overall health of the patient, frequently results in an inevitable death. A fall can also result in a fatal traumatic brain injury such as a subdural hematoma (a deadly brain bleeding). Some facilities may also use physical restraints as an inappropriate “fall prevention” method – for example, when bed rails are used to prevent an assisted living resident from falling out of bed. Bed rails present a significant safety risk because they often lead to fatal rail entrapments.

Bed sores (also known as “pressure ulcers” and “decubitus ulcers”) can also lead to tragic fatalities. Skin and underlying tissue breakdown leads to the introduction of bacteria and can lead to necrosis and fatal sepsis. Other infections – such as outbreaks of scabies [a very contagious skin infestation by the itch mite] and MRSA [Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus] – are common at nursing homes and assisted living facilities, and can be fatal. Dehydration and malnutrition due to elder neglect can also result in a fatality.

The subtle, yet just as significant, signs of elder abuse and neglect are:

- Skin injuries (e.g. cuts and bruises)

- Pain and general discomfort

- Disruptions and changes in sleeping patterns

- Anxiety, depression and feeling of helplessness

- Unwillingness to talk to anyone and withdrawal

Cherepinskiy Law Firm is the elder abuse attorney Los Angeles residents come to for guidance regarding signs of elder abuse and neglect.

Common Types of Elder Abuse & Neglect: In Long-Term Care Setting

These are the common types of elder abuse and neglect:

- Bed sores

- Dehydration

- Malnutrition

- Falls

- Infections

- Physical Restraints

- Chemical Restraints

- Sexual Abuse

- Physical Abuse

- Understaffing

Financial Elder Abuse

Elder abuse is not limited to just physical abuse or neglect in the setting of long-term care. When elderly people are taken advantage of by those who are in the position of trust and confidence – i.e. by caregivers, trustees, and beneficiaries – it constitutes financial elder abuse. If you suspect that your loved one has been taken advantage of, do not hesitate to contact a Los Angeles elder abuse lawyer.

Financial Elder Abuse by Caregivers

Frequently, when elderly people are no longer able to independently perform the activities of daily living (e.g. dressing, cooking, eating, ambulating / walking, transferring in and out of bed, dressing, grooming, etc.), they hire caregivers. As time goes on, a caregiver gains more and more trust of the vulnerable elderly individual. The caregiver “listens” to the lonely elder’s life stories and becomes a confidant. The caregiver may provide assistance with paying bills and performing other financial tasks. At some point, the elderly individual can provide the caregiver with access to all his or her financial and personal information, including bank accounts and checks, credit cards, as well as other personal and financial documents. This type of broad access to information creates a perfect opportunity for an unscrupulous caregiver to take advantage of the trusting elderly person and commit financial elder abuse.

Typical types of financial elder abuse by caregivers are as follows:

- Undue Influence on Estate Planning – i.e. inducing elderly to include caregivers in testamentary documents (such as wills and trusts)

-

- A caregiver may tell an elderly person, “I love you more than your own children. I am the one who takes care of you.” The caregiver may then convince, or even force, the elder to add the caregiver as a beneficiary to a will or trust. In some cases, the will gets “rewritten” so drastically that the caregiver becomes entitled to most of the elderly person’s assets, leaving almost nothing to children and grandchildren.

- Theft of Financial Assets

-

- Bank check fraud

- Writing bank checks as payable to the caregiver or some other third person / vendor and either forging the elderly person’s signature or convincing him/her that the check is going to be used for the elder’s needs

- Bank check fraud

-

- Stealing cash that is kept at the residence

-

- Identity Theft

- Using credit cards to make purchases (most frequently, online purchases)

- Making transfers from the elderly person’s bank accounts and other financial organizations (e.g. wire transfers, transfer of investments)

- Obtaining loans and creating new credit card accounts using the elder’s name and social security number.

- Identity Theft

- Theft of Real and Personal Property

Caregivers can steal the following from the elderly:

-

- Jewelry

- Paintings and other valuable items

- Cars

- By forging the signature on a title, the caregiver can acquire ownership of the elderly person’s luxury vehicle or an old classic car

- Real estate

- Yes, as unthinkable as it sounds, in some instances, caregivers managed to swindle elderly out of their own houses, condominium apartments and other properties.

- Inappropriate Fees

-

- Charging excessive fees, which are above and beyond the usual and customary rates for the type of service provided by the caregiver

-

- Charging fees for services, which the caregiver did not perform

- Practicing Medicine Without License

-

- A caregiver can falsely represent that he or she is a licensed healthcare provider (e.g. a registered nurse [R.N.] or a license vocational nurse [LVN]) in order to charge the elder’s Medicare or health insurance for “medical” services. This type of fraudulent activity is especially dangerous, because the unqualified caregiver can perform medical procedures or treatments that may injure the elder or may even be fatal. In fact, pursuant to California Penal Code section 2052, unauthorized practice of medicine is a crime.

- Inducing to Assign the Caregiver as Power of Attorney

-

- A caregiver may fraudulently convince the elderly individual to assign her or her as the Power of Attorney to “make things easier”. This is extremely dangerous, because the caregiver can then use these broad powers to easily commit the above-described types of financial elder abuse. Therefore, whenever a caregiver asks to be assigned as the power of attorney, it should always be a “red flag”.

The classic signs of financial caregiver fraud are as follows:

- Requests for a “power of attorney”;

- Making suggestions that the elderly person either transfer their financial accounts or open new ones;

- Making withdrawals from the senior’s bank account or making purchases out of that account;

- Requesting access or accessing elderly persons’:

- real estate;

- financial accounts;

- investments;

- testamentary documents such as wills and trusts;

- Trying to prevent the elder from communicating with his or her family and friends, and making efforts to completely isolate the elderly person;

- Withholding or hiding mail and various important documents from the senior;

- Recommending that the elder buy life insurance, health insurance, and other types of insurance.

Financial Elder Abuse by Trustees

A trust involves three separate parties:

(1) “grantor” or “settlor” – the individual who creates the actual trust and makes a transfer of funds into it;

(2) “beneficiary” – the person who is intended to “benefit” from the trust (i.e. receive the trust’s assets); and

(3) “trustee” – the individual whose task is to manage the trust.

In every situation where a grantor / settlor makes a transfer of money or property (i.e. assets) into a trust, the trustee gains control of the trust’s assets and has to manage them for the beneficiary’s benefit. In fact, the trustee’s power over the trust’s assets is so significant, that the trustee has the right to sell the assets, purchase additional assets, or take loans using the assets as a collateral. By law, the trustee must always act in the best interest of the beneficiary or beneficiaries and must never do anything that would jeopardize the trust. A violation of the trustee’s duties (also called “fiduciary duties”) can constitute financial elder abuse.

The trustee’s duties include, but are not limited to, the following:

- Interact with the beneficiaries in an impartial manner;

- Always comply with the trust’s conditions and terms;

- Make reasonable efforts to preserve the assets of the trust;

- Avoid any activity, which would create a conflict of interest with the obligations of the trustee;

- Avoid any use of the trust’s assets, which would benefit the trustee or result in the trustee’s financial profit; and

- In administering the trust and its assets, always act in the best interest of the beneficiary or beneficiaries.

Typical types of financial elder abuse by trustees are as follows:

- Inappropriate Gifts: Certain trust distributions are entitled “gifts”. In making these distributions, the trustee has an obligation to always comply with the trust’s terms, even if that means that certain beneficiaries receive smaller gifts that others. A trustee makes an inappropriate gift when the trustee picks a “favorite” beneficiary and, in violation of the trust’s terms, makes a larger distribution to that beneficiary.

- Asset Co-mingling: This type of abuse of the trustee’s powers happens when the trustee co-mingles (i.e. mixes) the trustee’s own assets with the assets of the trust. When this occurs, it becomes very challenging to clearly differentiate between the trust’s assets and the trustee’s assets. As a result, trustee may become unable to make accurate distributions in compliance with the terms of the trust.

- Collusion Between the Trustee and the Beneficiary occurs when they make a confidential agreement to violate the terms of the trust and provide the beneficiary with a larger distribution than dictated by the terms of the trust. For instance, the materialistic beneficiary may promise to share the “profits” of the inappropriate distribution with the unethical trustee.

- Embezzlement – is defined as a person’s misappropriation or theft of funds or assets, which have been entrusted to that person. Typically, it arises in the context of employer-employee relationships (for example, when a company accountant steals money from the company). In terms of trusts, embezzlement occurs when a trustee commits theft of the trust’s property, funds, or other assets.

- Self-Dealing – happens when the trustee violates his or her obligation to avoid the use of the trust’s assets for the trustee’s financial profit or benefit (e.g. when a trustee purchases a vehicle for himself or herself with the trust’s funds).

- Fraud: When a trustee makes a factual misrepresentation to a beneficiary or a grantor with the intention of inducing them to agree to a transaction that would benefit only the trustee, the trustee commits fraud.

Financial Elder Abuse by Beneficiaries

Beneficiaries can also be in a convenient position to commit financial elder abuse. Most frequently, this type of abuse is committed by will beneficiaries. Due to his or her close and special relationship with the individual who executes a will (a “testator”), there is a potential for a beneficiary to obtain significant benefits pursuant to the will (e.g. various assets such as money, securities, jewelry, as well as real and personal property). As a result, an unscrupulous beneficiary can be tempted to exert undue influence upon the testator or engage in a fraudulent activity with respect to the will.

Typical types of financial elder abuse by beneficiaries are as follows:

- Undue Influence: By law, in order for a will to be valid and enforceable, the testator has to execute the will voluntarily. Undue influence occurs when a will beneficiary forces a testator to make changes to the will, which would provide the “influencing” beneficiary with either (1) a disproportionally larger share of the assets than originally intended by the testator or (2) a larger share than would be fair under the circumstances. In order to achieve his or her goal, the perpetrator would withhold affection, threaten the testator, and utilize other types of psychological, emotional and, sometimes, even physical pressure upon the elderly testator. This is a classic example of undue influence (which is frequently shown in movies and TV series): A new and, typically, much younger, spouse convinces the elderly testator to bequeath to him or her the majority of the assets and leave to the testator’s children with a much smaller share than originally intended.

Senior people are especially susceptible to undue influence if they suffer from medical conditions that affect their memory and mental capacity, such as dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, schizophrenia and other conditions. If this type of abuse is discovered, the gift to the abusive beneficiary can be invalidated because the will was not executed voluntarily. In addition, this misconduct would constitute a form of financial elder abuse. People who can engage in financial elder abuse through undue influence include, but are not limited to, the following:

-

- parents

- stepparents

- children

- spouses (husbands and wives) and domestic partners

- fiancées

- business partners

- trustees

- attorneys

- pastors

- caregivers

- therapists

- healthcare providers – physicians, dentists, etc.

- students

- teachers

- Fraud in the Execution of a Will: This kind of fraud takes place when the testator believes that she or he is signing a will with certain provisions but, in reality, and unbeknownst to the testator, the will contains additional or completely different provisions. For instance:

-

- A beneficiary is entrusted with printing a will for the testator’s signature. Without saying anything to the testator, the unscrupulous beneficiary makes changes to the will that provide that beneficiary with a much larger share than intended.

-

- A beneficiary asks a testator to sign the last page of a new will, but makes a false representation that it is a completely different document (e.g. a business contract, a purchase agreement, etc.)

- Fraud in the Inducement happens when a beneficiary makes a false representation to a testator, and it induces the testator to insert certain provisions in the will. The beneficiary lies about facts that are material and important to the testator where, had the testator been aware of the truth, the will would have provided the beneficiary with a much smaller gift. For example:

-

- Misrepresenting the actual value of certain assets (e.g. making a statement about the testator’s expensive classic car that “this old piece of junk is not worth anything”);

-

- Falsely accusing another beneficiary of making disparaging comments about the testator (e.g. “your daughter says that she does not care about your health”); and

-

- Making a false representation to the testator that another intended beneficiary has already passed away.

Financial Elder Abuse by Those who hold the Power of Attorney

A “Power of Attorney” is a specific legal agreement, which allows one person (commonly referred to as an “agent” or “attorney-in-fact”) to act on behalf of another person (the “principal”). In general, this type of an agreement becomes invalid if the principal loses his or her mental capacity. However, a Durable Power of Attorney remains valid even in those situations where the principal has limited or no mental capacity. An agent holding the power of attorney has the right to make financial, legal, and medical decisions for the principal. In addition, the agent has virtually unlimited access to the principal’s personal and financial information, real and personal property, funds, and other assets. This type of a broad power to make financial decisions creates the potential, and a perfect opportunity, for financial abuse. Elderly individuals are especially susceptible to this type of abuse.

Typical examples of financial elder abuse by agents holding the Power of Attorney include the following:

- opening credit cards and bank accounts in the elderly person’s name but for the agent’s use and benefit;

- forgery of legal documents such as titles to real estate and vehicles;

- making purchases and entering into contractual agreements, which are intended to benefit only the agent holding the power of attorney;

- stealing funds from the elderly individual’s bank accounts; and

- removing the elderly individual from their residence by forcing him or her to move into an assisted living facility or a skilled nursing facility (nursing home).

Recoverable Damages in Elder Abuse and Neglect Cases

In general, plaintiffs in personal injury actions (including cases against elder care institutions) can claim the following two main types of damages: Non-Economic and Economic damages. A detailed discussion of the recoverable damages is included on the Personal Injury Damages page of this website.

In terms of recoverable damages in elder abuse matters, California law allows potential recovery of certain “enhanced” remedies when:

(1) physical abuse or neglect is proven by clear and convincing evidence; and

(2) a defendant nursing home or assisted living is found to be guilty of committing elder abuse with fraud, malice, oppression, or recklessness.

-

- “Fraud” occurs when a defendant: (1) intentionally engages in deceit or misrepresentation, or conceals a material fact that the defendant is aware of and (2) the defendant’s conduct is intended to deprive an individual of legal rights or property or cause an injury that individual. California Civil Code 3294(c)(3);

-

- “Malice” refers to a defendant’s conduct, which: either (a) is committed with a “willful and conscious” disregard of other people’s safety or rights; or (b) is specifically intended by the wrongdoer to cause the plaintiff’s injury. California Civil Code 3294(c)(1);

-

- “Oppression” is defined as despicable conduct, which: (1) subjects an individual to “cruel and just hardship” and (2) is committed with a conscious disregard for the victim’s rights. California Civil Code 3294(c)(2); and

-

- “Recklessness” means a level of culpability that is greater than mere negligence – i.e. it entails more than incompetence, inadvertence, a lack of skill, or a failure to take appropriate precautions. Recklessness involves a “conscious choice” of a specific course of action and a “deliberate disregard” of the “high degree of probability” that the conduct will result in an injury. Delaney v. Baker, 20 Cal. 4th 23, 31-32 (1999).

When the above requirements are established, the recoverable enhanced remedies are as follows:

- if the victim of elder abuse dies, unlike other matters where Survival claims are asserted, recovery of pre-death pain and suffering of the deceased person is allowed;

- attorney’s fees can be recovered; and

- punitive damages can be imposed on a defendant as well.

California Welfare & Institutions Code § 15657. Pursuant to section 15657(c), for these enhanced damages to be available against a defendant nursing home or assisted living facility, the requirements of California Civil Code § 3294(b) must be satisfied – i.e. it must be established that the facility:

1. knew that an employee nurse or a caregiver was unfit (e.g. unqualified) for the position and employed that person “with a conscious disregard of the rights or safety of others”; or

2. authorized or ratified (approved) the wrongful conduct of the employee(s); or

3. someone in the position of authority was personally guilty of oppression, fraud, or malice.

Finally, if elder abuse on the part of a nursing home or assisted living facility resulted in the death of a loved one, then compensation can be sought in a Wrongful Death action.

In order to navigate through the complex process of evaluation of damages, you need the assistance of a Los Angeles elder abuse attorney who is the top specialist in the field.

Elder Abuse is a Crime

In addition to the civil remedies, those who commit elder abuse may be subject to a criminal prosecution. California Penal Code § 368 makes it a crime to engage in the emotional or physical abuse, neglect, or financial exploitation of the elderly.

It is a crime to intentionally, or with criminal negligence, subject a senior individual to unjustifiable physical pain or mental suffering if the defendant knew or should have known that the elderly victim was 65 years old or older. This crime can be prosecuted either as a felony or a misdemeanor – depending on specific circumstances and how likely it was that the defendant’s misconduct would result in the elderly person’s great bodily injury or death. This law also covers financial crimes against the elderly, including theft, embezzlement and fraud. If the victim was the victim is 70 years of age or older, offenders will face longer prison terms.

Prevention of Elder Abuse and Neglect

Family members and friends of the elderly can take steps, which can help with the prevention of elder abuse and neglect:

- When you are visiting your loved one, observe your surroundings and watch for signs of inadequate staffing or neglect (e.g. if you hear patients in neighboring rooms make repeated pleas for help or assistance, which are left unattended for extended periods of time).

- Observe how frequently your loved one is being cleaned, turned and repositioned (if he or she is not mobile).

- If you see any changes in the elder’s mental status or the level of physical activity, ask if any psychotherapeutic medications are routinely administered to him or her. Some psychoactive medications may not be given without the patient’s or a responsible party’s consent.

- In general, check whether the medications given to your loved one correspond to the physician’s prescriptions.

- Make efforts to frequently visit your loved one at a nursing home or assisted living facility. Unscheduled visits are always better, because they provide an opportunity to potentially “catch” the wrongdoers “in the act”.

The Firm Builds Strong Elder Abuse and Neglect Cases

As the Los Angeles elder abuse lawyer, Cherepinskiy Law Firm utilizes the most effective strategies to discover all the necessary evidence and present the strongest possible cases for the victims of elder abuse and neglect. These strategies include, but are not limited to, the following:

- Requesting and evaluating facility medical records such as:

-

- Assessments;

- Care plans;

- Nursing notes;

- Flowsheets;

- Physicians’ progress notes;

- Physical therapy notes;

- Occupational therapy notes;

- Orders;

- Treatment Administration Record (TAR);

- Medication Administration Record MAR);

- Photographs; and

- Long Term Care Minimum Data Set (MDS) [standardized assessment and screening used by nursing home for Medicare compliance purposes]

- Requesting and evaluating business and administration records such as:

-

- Policies and Procedures;

- Staffing and scheduling documents;

- Video surveillance recordings; and

- Documents regarding business expenses and employee salaries

- Obtaining public records from the Medicare, California Department of Health Care Services, Department of Social Services, as well as local health departments, including:

-

- Surveys;

- Complaints;

- Deficiencies;

- Citations; and

- Investigations.

Take Action! Contact a Los Angeles Elder Abuse Lawyer for a Free Consultation

As an aggressive Los Angeles nursing home neglect lawyer, Dmitriy Cherepinskiy, and his firm, tirelessly pursue justice. If you or your loved one fell victim of physical restraints or chemical restraints, or sustained injuries due to falls, bed sores, or infections, this firm will serve to vigorously vindicate your rights. If elder abuse or neglect in the hands of an assisted living facility has caused the death of a loved one, the Los Angeles assisted living neglect lawyer will fight relentlessly in a wrongful death case.

If you suspect nursing home neglect or elder abuse, please call or fill out an electronic contact form today to request a free consultation. Cherepinskiy Law Firm, as the Los Angeles nursing home abuse attorney, will work tenaciously to bring the wrongdoers to justice, and to obtain the maximum case value and compensation you deserve.

This firm fights for clients throughout California, including Los Angeles, Orange County, as well as Ventura, Riverside and San Bernardino Counties.

Resources

1. https://oag.ca.gov/bmfea/elder

2. https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CHCQ/LCP/CalHealthFind/pages/home.aspx

3. https://www.cdss.ca.gov/inforesources/Senior-Care-Licensing